Snake Antivenom (AV)

Seyed Shahmy - National Science and Technology Commission of Sri Lanka (NASTEC)

A precise treatment for exposure to a poison or toxin resulting from a bite or sting from an animal such as a snake, scorpion, spider, or insect or from marine life is antivenom (AV), also referred to as antivenin and venom antiserum. Only when there is a significant amount of toxicity or a high risk of toxicity are the AVs indicated for treatment of certain venomous bites and stings made up of antibodies. Depending on the species involved, a particular AV may be required. It is given by injection.

There are side effects that could be reported due to the pyrogenic contamination of the AV (an impurity of the product—a challenging task encountered during the production process), and these may vary from mild to severe anaphylactic reactions such as rash, itching, wheezing, rapid heart rate, fever, body aches, hypotension, difficulty in breathing etc.

AV is traditionally made by collecting venom from the relevant animal and injecting small amounts of it into a domestic animal. The antibodies that form are then collected from the domestic animal’s blood and purified. Versions are available for snake bites, spider bites, fish stings, and scorpion stings. Alternative techniques for generating AVs are being actively researched due to the high cost of producing antibody-based AVs and their short shelf lives when not refrigerated. Such an alternative production technique uses microorganisms and different strategies to create targeted medicines, which, unlike antibodies, are typically synthetic and simpler to produce in large quantities.

History of Snake AV.

In 1894, Albert Calmette, a French physician, bacteriologist, and immunologist, successfully created an anti-cobra serum in rabbits. His work had an international impact on researchers and transformed the way that snakebite envenomation was treated.

AV manufacturing has mostly stayed unchanged for more than 120 years. A small amount of venom is injected into the animal, resulting in an immune system reaction and the release of antibodies, which are later extracted by bleeding. The majority of AVs are produced in horses, while some are also produced in sheep. After being concentrated and purified, this blood plasma is used to create pharmaceutical-grade AV. While the fundamental production process hasn’t changed much, numerous technological innovations and purifying techniques have been added to produce items of higher quality and minimize adverse effects.

How to make AV step by step

In a typical antivenom centre, different species of snakes are raised, cared for, and continuously watched over to ensure they are in good health. Professionals bring the snakes—which may include some of the deadliest—into a milking room when the time is right. The venom glands are located at the very rear of the head, directly behind the angle of the jaw, where the snake is caught with the thumb and index finger. Despite the fact that many expert snake handlers get bitten numerous times over their careers, this permits the snake milker to massage the snake’s glands without the snake turning around and biting.

Even seasoned specialists can only milk a very small amount of venom from a snake, thus it takes many, many milkings to obtain a usable amount. The venom must be milked, chilled to below -20 °C, and commonly freeze-dried for convenience in storage and transportation. By removing water, this technique also concentrates the venom. Naturally, each vial of venom needs to be accurately tagged with the type of snake, its location, and other information. The portion about vaccinations follows.

Because they survive in a variety of environments around the world, have a huge body mass, get along with other animals, and are sufficiently accustomed to humans that they aren’t readily terrified by the injection process, horses are traditionally used to produce antibodies. As well as donkeys, rabbits, cats, chickens, camels, and rats, goats and sheep are also used. Some institutions even conduct shark experiments. Sharks can create quite potent AV, although for obvious reasons, it is rarely employed.

Venom injecting to a Horse

Chemists quantify the venom precisely and combine it with purified water or another buffer solution before injecting the animal. In order for the horse’s immune system to respond and develop antibodies that attach to and counteract the venom, an adjuvant is most crucially added to the solution. A veterinarian constantly monitors the procedure to ensure the horse’s (or other chosen animal’s) health. The bloodstream antibodies of the horse often reach their peak in 8 to 10 weeks. The horse is now prepared for blood collection, which usually involves draining 3 to 6 liters of blood from the jugular vein.

Purification is the next stage of the AV production process. The blood is next centrifuged to separate the AV from the plasma, the liquid element of the blood that is devoid of blood cells. Producers generally use their own techniques during this stage, many of which are considered a trade secret. However, undesirable proteins are normally eliminated through precipitation by either modifying the pH of the plasma or incorporating salts into the solution.

Plasma separation

One of the last steps in AV preparation involves using an enzyme to break down the antibodies and isolate the active ingredients. The last step is usually checked by an outside regulatory body like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, or FDA, in the United States (in Sri Lanka, it is ideal to be the National Medicinal Regulatory Agency, or NMRA). Once approved, the samples are concentrated in powder or liquid form, then frozen and shipped to hospitals where they’re most needed. As you can see, the process is extremely complicated, expensive, and of little yield.

Snake AV Production in a Nutshell

Did you know?

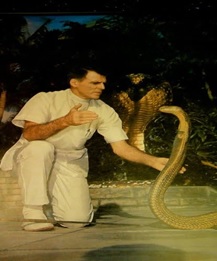

William Haast at his Miami Serpentarium in the 1950s (Figure Credit: The New York Times)

- A well-known snake handler Bill Haast, who passed away at age 100, was renowned for milking more to 100 snakes per day. At this rate, it’s conceivable that he would have frequent bites. After realising this, he started injecting himself with diluted cobra venom in 1948 to build up his own immune system. Haast had already survived 172 bites from many of the world’s deadliest snakes, including a blue krait, a king cobra, and a Pakistani pit viper, before he passed away from natural causes. Even travelling across the globe to donate blood for direct transfusion, he helped save 21 victims.

- Because horses can thrive in a variety of environments worldwide, have a huge body mass, get along with other animals, and get along with each other, they are frequently used as animals to produce antibodies. Sheep and goats are equally effective. Donkeys, rabbits, cats, chickens, camels, rodents, and even sharks have all been utilized by researchers.

- Based on the type of antigen utilized in manufacture, there are primarily two categories of AVs, namely Monovalent and Polyvalent. It is referred to as a monovalent AV if the hyper immunizing venom comes from a single species. The makeup of the antivenin is referred to as polyvalent if it contains neutralizing antibodies produced against two or more species of snakes.

- The AV, which is available in Sri Lanka for snakebite treatments, is made in India. The Indian polyvalent antivenom available here contains mixtures of antibodies against Cobra (Naja naja), Russell’s viper (Daboia russelii), saw-scale viper (Echis carinatus), and Common krait (Bungarus caeruleus) bites.

- There is research going on in Sri Lanka to develop its own AV that could also contain the antibodies against hump-nose viper bites (Hypnale hypnale), which are lacking in the current available Indian AV in Sri Lanka, in addition to the venoms against the above-mentioned four snake types.

- Usually 10–20 vials of Indian AV are needed to treat each envenomed snakebite patient locally (diluted in 400 ml of normal saline for adults over one hour; total volume 500 ml; and 10 vials diluted in 100 ml of normal saline for children over two hours; total volume 200 ml of intravenous slow infusion).

Glossary:

- Antibodies- are proteins that protect you when an unwanted substance enters your body

- Envenomation- is the exposure to a poison or toxin resulting from a bite or sting from an animal such as a snake, scorpion, spider, or insect, or from marine life.

- Freeze drying- is a process in which a completely frozen sample is placed under a vacuum in order to remove water or other solvents from the sample, allowing the ice to change directly from a solid to a vapor without passing through a liquid phase

- Jugular vein – carries blood from a horse’s head back to its heart. It is located within the jugular groove, on the lower side of the horse’s neck

- Hyper immunization- is the presence of a larger than normal number of antibodies to a specific antigen. This creates a state of immunity that is greater than normal.

- Pyrogenic- substances that can produced by heat or fever- endotoxins

- Serpentarium an enclosure in which snakes are kept.